23 March 2021

Uncategorized

Time is a luxury. A commodity which stands in stark contrast to the current socio-economic situation challenging developing countries. Indistinct land tenure, rapidly changing climatic conditions, and limited access to information pose serious challenges when it comes to guaranteeing food security in Sub-Saharan Africa, and growth in agricultural productivity is a starting point in tackling this task.

Lack of knowledge and persuasiveness of corporate lobbyists often lead African farmers to choose short-term solutions over durability. The heavy usage of agrochemicals has resulted in unprecedented negative outcomes for soil, animals and humans, and thus prompted regulatory (and overdue) debates across the globe

Yet, time is pressing for small-scale farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Decisive discussions are being held on a higher political and economic level, whereas farmer’s opinions are only being acknowledged due to the persistent work of advocacy groups of NGOs, such as Biovision.

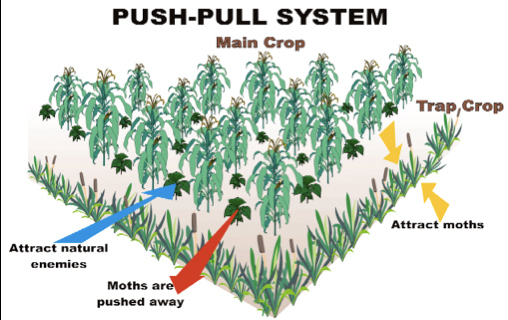

Meanwhile, the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) in Kenya promotes the Push-Pull method – a holistic approach on facing the looming problems in agriculture. The method was developed in consultation with farmers, and adapts technology and research in order to meet their needs.

Push-Pull is an integrated, sustainable method of farming that increases yields by controlling pests, retaining soil moisture, and improving soil fertility in a natural way. The legume Desmodium is planted as an intercrop between the maize or millet and its smell repels the stemborer moths – Push. The soil’s capacity to absorb and store moisture is enhanced, nitrogen is absorbed and, consequently, soil fertility is improved.

In addition, Desmodium decimates the parasitic Striga weed and thus increases yields.

A fodder grass is planted as a border crop; it draws the moths away from the field – Pull – where they lay their eggs. Once hatched, the

moth larvae suffocate on the sticky sap released by the leaves of the grass. In the conventional Push Pull set-up, Silverleaf desmodium (Desmodium uncinatum) is used as a push agent while Napier grass (Pennisetum purpureum) is used as the border crop.

Both Napier grass and Desmodium are also a source of healthy animal fodder. In addition to being effective against the stemborer moth and striga weed, the Push-Pull method has also proven its value in the ongoing fight against the fall armyworm – the larvae of the invasive moth – Spodoptera frugiperda. In May 2017, a farmer from Western Kenya reported to icipe, that his maize fields, using the Push-Pull method, were largely spared by the effects of the fall armyworm in contrast to his pesticide-fertilized fields, where the damage was vast. Similar reports came from a female farmer who lives 350 kilometers away. She stated that the conventional maize fields were totally overrun by the fall armyworm, whereas the Push-Pull fields of her mother-in-law, just 30 meters away, remained largely unharmed.

By simultaneously contributing to the health of plants, soil, and living organisms, Push-Pull offers us a glimpse of how sustainable agriculture can be practiced, even under unfavorable environmental conditions. Exchanges of energy and resources in an ecosystem are sustained by cooperation, not competition.

Many people in rural East Africa earn their living from farming; the majority are families living on smallholdings with little land. Pests, leached soils, and excessive aridity are making life difficult for farmers, who lack the knowledge of suitable methods to increase crop yield. The Push-Pull method can offer relief, as its wide range of effects can increase yields up to 300 per cent.

After developing the method in the nineties, Push-Pull has gained a lot of momentum in Eastern Africa. Since the Biovision Foundation started to support and spread the technology in Kenya, the technology has expanded: After spreading to neighboring countries such as Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia, Push-Pull has established itself outside of East Africa in countries like Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Burundi and Burkina Faso. A total of about 150,000 small-scale farmers in the different project regions are currently benefiting from the various activities of the Push-Pull programme.

Although increasingly popular, Push-Pull has yet to enter the mainstream in farming-technology. Agroecology is steadily gaining acknowledgement due to thorough research processes and various evaluation procedures. Credibility is key in a highly contested market like agricultural technologies.

Since entering the agricultural arena, Push-Pull has proven itself to be an influential method beyond the agricultural segment and is seeming to be the mere starting point in vast structural changes for farmers in rural areas of East Africa. With help from local partnerships, Biovision is facilitating workshops and meeting groups, in order to explore potential synergies in marketing, distribution, and processing of surplus crops.

Meanwhile, researchers are exploring new combinations of plants and furthering development and evaluating local push or pull plants. Just last year, icipe received a message from Zimbabwe. Farmer Jona Mutasa, who asked icipe back in 2008 for a manual on how to practice Push-Pull eventually became a prominent trainer, leading over 2,000 other farmers to adopt the technology.

The aim to increase food security and incomes by accelerating the spread of the Push-Pull method is a complex undertaking. While time is luxury, a good thing is worth waiting for.

Written by: Stefan Diener – Biovision Foundation

Published by: Fair Planet

Images by: Peter Lüthi.